Blake and Mortimer’s resurrection is an interesting phenonomen. Edgar P Jacobs was at the forefront of the development of the cartoon in the forties and fifties, as he worked with Hergé, who pushed the boundaries of the new medium.

Hergé’s last complete book was in the seventies and Jacobs died in the eighties. It was not for two decades that Blake and Mortimer were brought back to life, and those years had seen many changes in cartoon books, or graphic novels, as they had come to be known. The medium had matured, and artists were tackling much more ambitious subjects. The gag, that underpinned early comics, was now all but gone, and the flippant tone, aimed only at children was replaced with serious subject matter, such as the Holocaust, in Art Spiegelman’s Maus.

The evolution, started by Hergé, had continued throughout the sixties with Robert Crumb, through to the eighties, with Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns, bringing even more complex themes, plots and characters.

The new Blake and Mortimer books reflect the new readership, of a generation brought up on these books. Characters have a past which sometimes catches up with them (The Oath of the Five Lords), old flames that they reconnect with (The Gondwana Shrine) and in interest in the opposite sex that Tintin and indeed the old Blake and Mortimer never did.

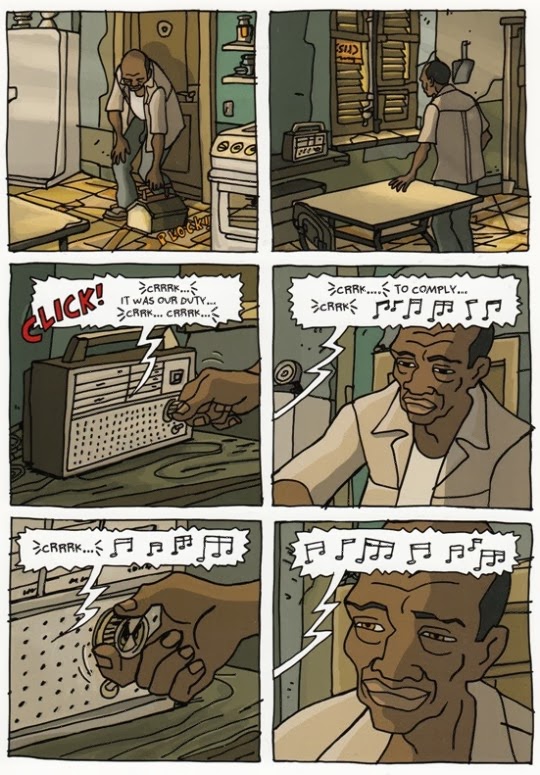

The Voronov Plot is an absorbing cold war thriller, that gives James Bond a run for it’s money. The plot stays on the right side of credible (unlike The Gondwana Shrine), and is, with the benefit of hindsight, is a little more gracious to the Soviet Union than many novels and comics produced during the cold war.

The book also features interviews, not only with the artist and writer, but also the colourist, which give a valuable insight into the creative process. They talk about their Hergé tributes (if you do not spot them they are revealed in the interview section at the end), and the colourist talks about the challenges of colouring a work like this, and how the eye of the reader has changed since the first books came out, over 60 years ago.

This is one of the best of the new Blake and Mortimer books that I have read, and if I was to compare it to one of the Tintin books it would be The Calculas Affair, one of Hergé’s best.

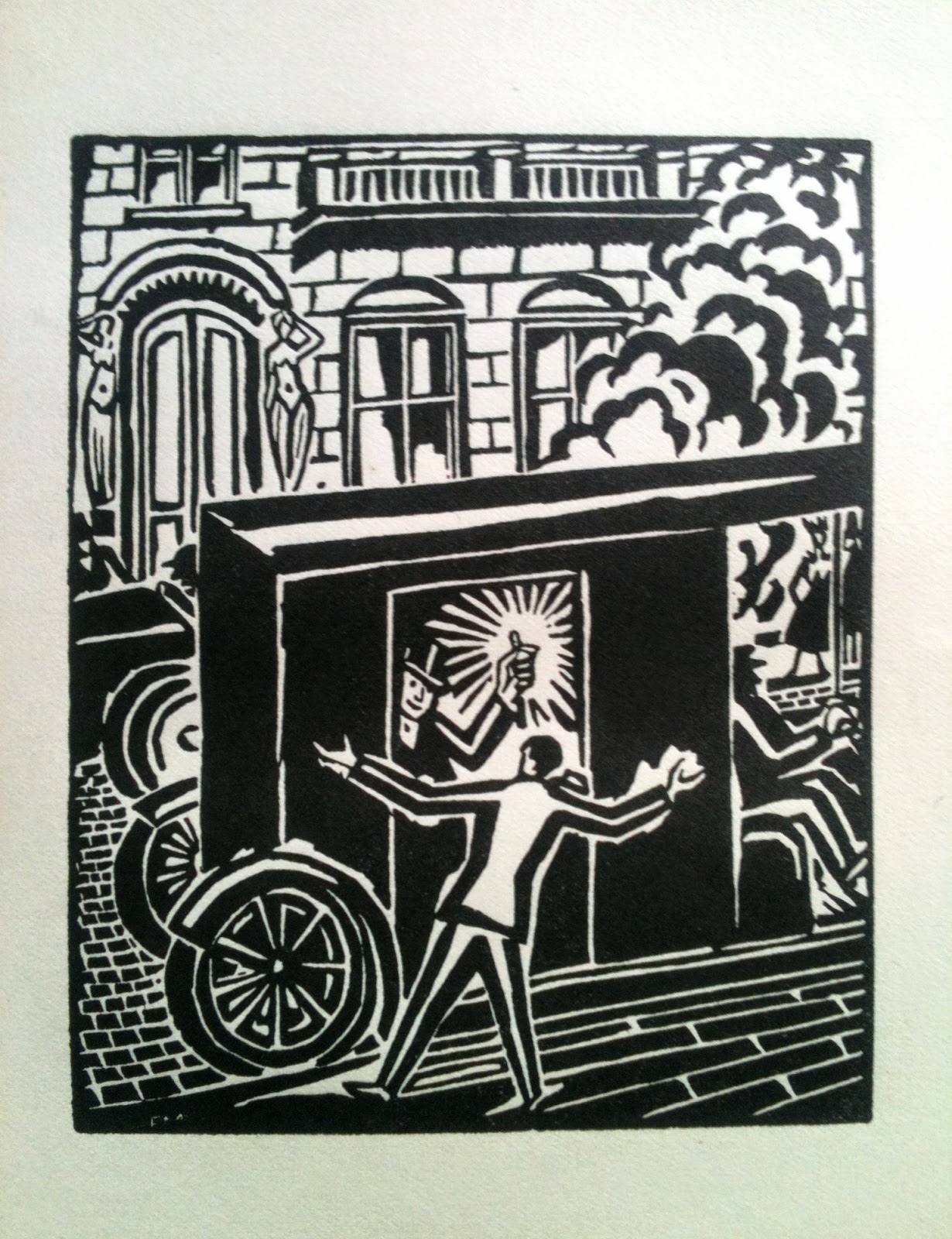

There are also figurines available, such as this one of Olrik, in his Russian uniform, costing 850 euros.